By Mary Afemata of Local Democracy Reporting

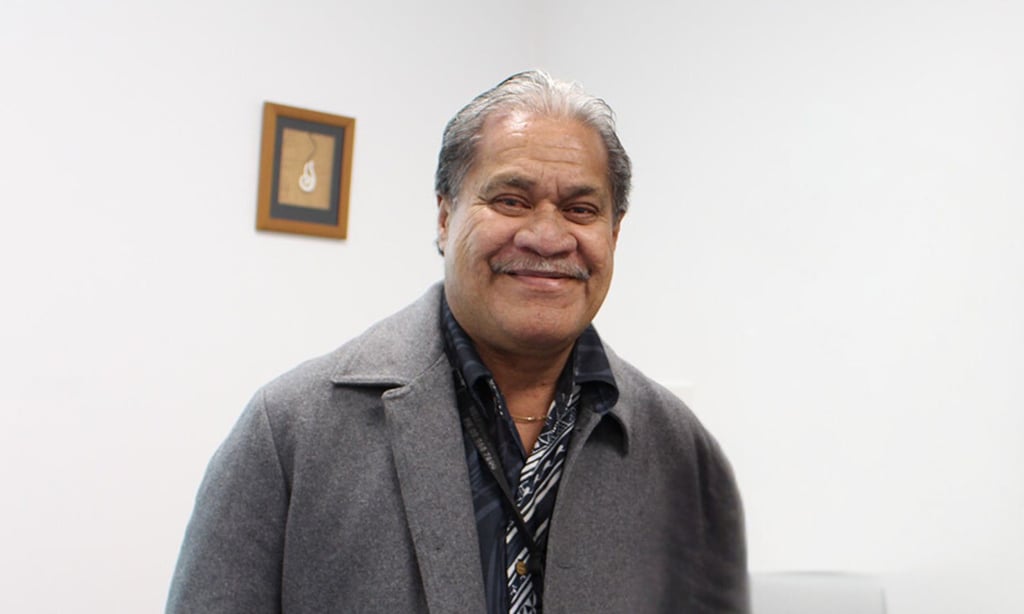

A Sāmoan community leader and educator was stunned to see former students step forward as potential kidney donors, following a public appeal.

For 20 years, Tauanu’u Perenise Sitagata Tapu has been a respected teacher at McAuley High School and in the community.

He struggled with diabetes and kidney failure for decades, and despite being asked to consider a kidney donor multiple times, had accepted his situation.

“I look at it this way: the Lord gave me life. I’ve lived a good life. I accept what’s happening in my life.

“I do not want any other person’s life shortened because they have to help me. That was simply my view. I will accept any time that I [might] leave this world, but I also accept the life that I have now.”

However, his son changed his mind after a hospital nurse, also of Pacific descent, shared how she had donated a kidney to her 80-year-old mother, who was still thriving at 85.

Although uncomfortable with going public, Tauanu’u’s children said it would help, and posted a public appeal on Facebook.

“We now look beyond our family… If there is help out there, we welcome it with open arms, so that Dad might have more life to serve our communities, especially our young people.”

Twenty-seven people stepped forward to see if they were potential donor matches, with five being former students.

“I must have been a damn good teacher,” he laughed, but added he was “very, very grateful.

“There was a list given to me—some ex-students, about four or five, and a couple [of others] I know, but the rest I don’t know.

“I’ve managed to contact each and every one of them to thank them.”

A long struggle

Tauanu’u’s health journey began in 1997 when he was admitted to Middlemore Hospital with severe pancreatitis, spending 44 days in the ICU and nine months in hospital.

“They had removed my pancreas, gallbladder, and spleen. I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, which required daily injections because the pancreas is gone.”

He has had daily injections ever since and started insulin in 2012, before beginning dialysis in 2014, which happens three times a week.

From here, the hospital will coordinate directly with the contacts, and Tauanu’u will be notified if a suitable donor is found.

“I’m not [mentally] affected by waiting; I’m used to it. I’m still walking the journey of dialysis every week, and I’ll keep doing that until I hear from the hospital. It’s been part of my life, and I’ll continue with it,” he says.

While grateful for those who have stepped forward, Tauanu’u is still waiting for a viable match. The community has responded, but the challenge lies in finding a suitable donor.

His family continues to appeal for potential donors. Interested individuals can contact his son, Neil Tapu, at [email protected] to test their suitability.

Addressing medical and cultural barriers

In New Zealand, Māori and Pacific communities have the highest rates of diabetes and related complications, such as kidney failure.

Tauanu’u said conversations around organ donations are still relatively new within Pacific families, but should be normalised.

“If someone needs an organ, it would typically come from immediate or extended family—that’s it. But it should be broader—it should be like what I’ve done, and maybe I’m one of the few Pacific elders going public on social media.”

Dr. Amelia Tekiteki, a renal specialist at Auckland City Hospital, said Pacific and Māori people experience kidney disease at younger ages compared to other ethnic groups that are non-Māori and non-Pacific.

“Māori and Pacific have the highest rates of ‘severe diabetes,’ which is diabetes linked to complications like amputations and kidney failure.”

Tekiteki’s research showed many are reluctant to accept organ donations from family members due to guilt and cultural beliefs.

“It’s just feelings of guilt, like ‘This is my problem, I don’t want to burden [anyone]’, and some patients felt like, ‘I don’t want to take it from my children because what if, their grandchildren need a kidney in the future?’”

Tekiteki said when it comes to receiving transplants, Pacific patients face inequity in receiving one.

“Poor communication from healthcare professionals, feelings of perceived racism, financial limitations and constraints, which impact their access to attending clinics.

“Some people don’t want to go through dialysis because it’s a big undertaking.”

Tekiteki called for more education about kidney donation within Pacific communities, along with more awareness and open discussions.