This article was first published in Cook Islands News and has been republished with permission

When she was in her 20s, Marjorie Crocombe was barred from Australia by its racist immigration policy. Now, as Cook Islands’ most venerated living author turns 90, she switches off the TV news coverage of BlackLivesMatter protests, and wonders how much has really changed. She talks with Katrina Tanirau.

One of the hardest jobs a journalist will ever undertake is interviewing a writer and academic.

Some say, you need to be a “jack of all trades” to do this job, learning as you go.

Dr Marjorie Tuainekore Tere Crocombe has spent her life on a journey of learning, inspiring and educating others.

It’s hard to imagine that the woman of smart wit, sitting with coffee in hand, a small notepad with ideas jotted down and a folder with notes on the current saga at the University of the South Pacific is a day over 50 years old.

But next week, she celebrates her 90th birthday.

Her children want to make a song and dance about it, but she is not too fussed.

“I really don’t want anything big,” she says.

Like most who have achieved great feats, it’s obvious that Crocombe is more focused on other people as opposed to wanting to talk about herself.

“So what would you like to know?” she says.

“Everything,” I reply.

And so the words flow.

A sandalwood tree that stands tall at the back of Marjorie Crocombe’s property, tells the story of where her fascination with history began.

In 1813, an Australian ship captain, Theodore Walker returned to Sydney with a tale about an island in the South Pacific that was covered with sandalwood trees – growing from the shores to the very tops of the mountains.

Although he never ventured onto the shores of Rarotonga, he named the island Walker’s Island.

While up in court on a charge of hanging a seaman on board his ship, Walker shared his story with the court’s magistrate D’Arcy Wentworth.

In 1814, the Cumberland with Wentworth on board set off on a mission to fund the sandalwood trees, which at the time could “make a man rich for the rest of his life”.

Ultimately, not one sandalwood tree was found on Rarotonga.

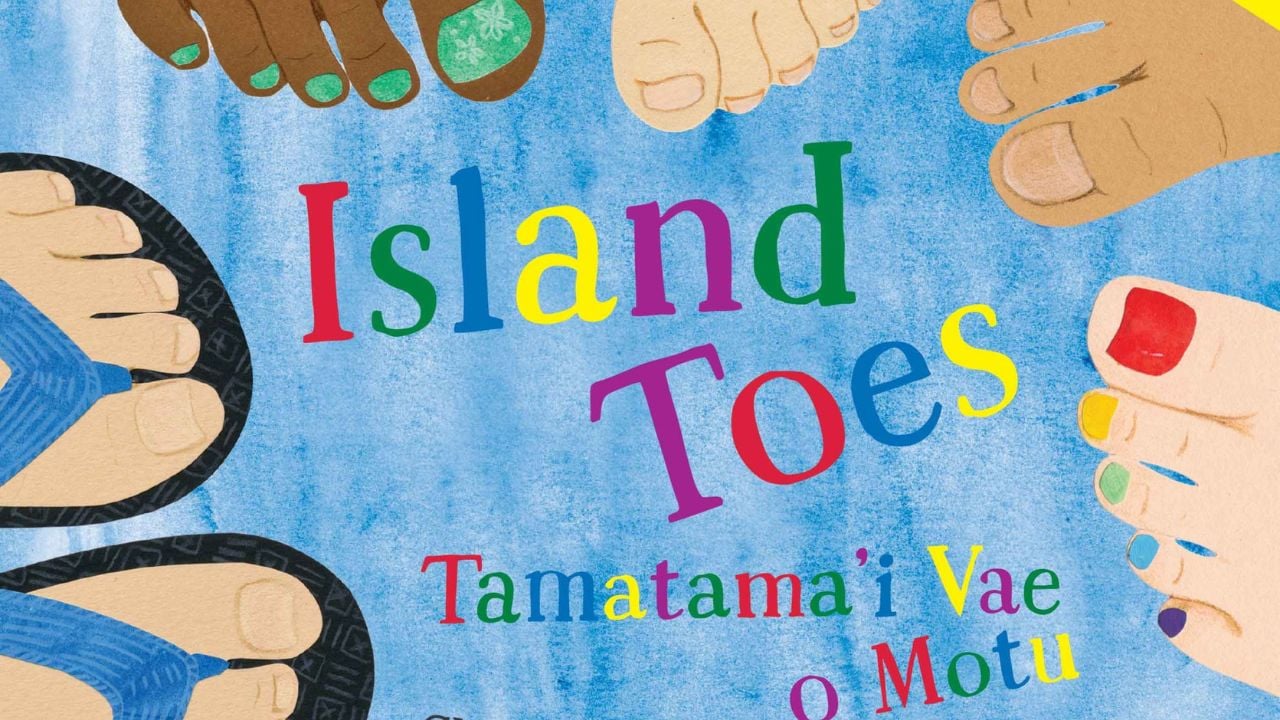

Crocombe’s book They Came for Sandalwood was the culmination of her research into those events, she has authored many books that have been used by schools and universities as educational resources.

One day, a young man turned up at her home with the sandalwood tree.

“He said to me I thought you would like this,” she says.

History she says, can only be told properly by the people of the land – their stories, in their own words and language.

Crocombe also has an advantage when it comes to being able to go back and research the history of her ancestors. She can speak Cook Islands Maori fluently and has been given access to manuscripts detailing local versions of the history that had largely been written by Europeans.

Born on June 19, 1930, Marjorie Crocombe was the youngest of 11 children.

They grew up in Titikaveka back in the days when there was a lagoon full of fish and shell fish, a cow for milk, chickens, plantations.

She can’t ever remember when there was a shortage of anything.

One of the first stories she wrote, Bush Beer was inspired by her six rugby playing brothers who whether they “won or lost” would mix a brew in an old tin can and “celebrate”.

Marjorie Crocombe and her husband the late Professor Emeritus Ronald “Ron” Gordon Crocombe met at a dance in Rarotonga in 1955.

He had spent time working in Aitu and was on his way back to New Zealand and asked if she would join him.

“I said to him no way! For a start I don’t even know you,” she says.

“He said to me we can get to know one another on our way back to New Zealand.”

Crocombe hated boats, the first time she went to New Zealand, she recalls lying flat on her back most of the way.

But their paths linked again a year later, they were married and their children Tata, Nari and Kevin followed soon after.

Being the wife of an academic, you had to look bright, she says.

At times she could do only one university paper, but her and her husband shared an unfathomable love of education, especially Pacific studies.

In 1967 while living in Papua New Guinea, Crocombe signed up for two papers at the University of Papua New Guinea – one in Papuan history and the other in creative writing.

“For the history paper I had to drive six miles,” she says.

The creative writing papers had to be written at home and submitted to the Nigerian professor once a week.

So she thought: “Well I’ll start writing about the Cook Islands.”

Her professor encouraged her to start a writers’ group.

Later on, her stories and those of other Pacific Islanders were published in the Journal of the Polynesian Society.

She is regarded as a champion of oral poetry and literature, and outspoken about encouraging Pacific writers to analyse contemporary life through poetry, art and stories.

In 1969 the University of the South Pacific opened and Ron Crocombe got a job as the Professor of Pacific Studies.

Ron’s job took them all over the world. Papua New Guinea, Canberra Australia, the United States and Fiji.

But Rarotonga was always “home”.

In June 2009 while on their way home from Auckland, Ron Crocombe passed away suddenly.

He was so loved and respected, he was referred to as “the father of Pacific studies”.

Marjorie Crocombe paid the ultimate tribute to her husband in 2014 when she co-wrote and edited a book about his life entitled: Ron Crocombe: E Toa: Pacific Writings to Celebrate His Life and Work.

Marjorie Crocombe has achieved a lot of firsts in her life.

She was one of the first Cook Island students to receive a scholarship to New Zealand to finish her secondary school education at Epsom Grammar School and later Whanganui Girls College.

“At the end of the Second World War they decided to set up this scholarship – there were three boys and me.”

After completing her schooling, she went to Ardmore Teachers Training College for two years and then returned to Rarotonga, where she worked for the Cook Islands Education Department.

In 1971 she was one of two Cook Islanders, the other Lionel Brown to graduate from the University of the South Pacific, and then went onto study Pacific Studies and Sociology at the University of Hawaii, University of Papua Guinea and University of California, Los Angeles.

Crocombe has held various lecturing roles at USP including during the Fiji coup in 1987, was a senior lecturer at the Centre for Pacific Studies at University of Auckland and has taught at institutions in China, Australia and Hawaii.

In 2011, Crocombe was the first woman from the Cook Islands to receive a Doctor of Letters (honoris causa) from the University of the South Pacific.

Being brown and a woman have been the driving forces behind Crocombe’s desire to make a difference for Cook Islanders and indigenous people around the world and the issues she is passionate about.

It wasn’t until many years later that she realised she had been instrumental in New Zealand Maori girls being able to complete their secondary school education at Whanganui Girls’ College.

When she thinks about it now, there were only three students that weren’t European when she was at the college.

She used to wonder why “Miss Baker” would come to see her every night to see how her studies were going.

“All those years later I finally realised what she was doing, she had been fighting with the school’s board of governors to allow Maori girls to attend the school,” she says.

“There was so much racism back then.”

In the late 1950s Crocombe says she wasn’t granted entry into Australia initially, because of the White Australia Policy.

Experiences like this cemented her determination to succeed in a world where the colour of her skin influenced how far in life you would get.

Today, watching the unrest unfolding in the United States and around the world in relation to the #BlackLivesMatter movement is hard for Crocombe.

“I switch the TV off,” she says.

Only time will tell whether the world will ever be able to live in harmony, Crocombe says.

“I’ve always encouraged writers and artists to find their voices through their stories or art,” she says.

“It’s a great way to express yourself.”