In a quiet South Auckland industrial estate, the diminutive figure of American anthropologist Robert Borofsky holds court.

He’s here with members of the Te Ulu O Te Watu Society (TUOTWS) in Auckland, a group made up of families from the island of Pukapuka, an atoll in the northern Cook Islands.

“It’s just for me, a sense of obligation, here’s these people who’ve put up with me for 41 months and let me ask all these questions,” Borofsky says.

Based in Hawaii and now retired, the author and academic lived on Pukapuka from 1977 to 1981 with his wife and young daughter.

“They allowed me to stay there with my family, my wife Nancy and daughter Amelia. And they allowed me to collect all this information, he says.

“They were very open to answering questions and I think really, I was morally obligated to give them back the field notes.”

During his time in Pukapuka Borofsky collected some 16,000 pages of research notes which also included audio recordings with informants. He’s already published a book on his time there and he’ll make his field notes available on his website, publicanthropology.org.

The term ‘Public Anthropology’ was coined by Borofsky to express his desire for information to be more readily accessible to communities studied by academics. He says there’s a lot society can learn from other communities and their differences.

“Anthropology in some ways is going on hard times, it’s become too academic, they write and go into some abstract perspectives but the basic message of anthropology is extremely relevant today, certainly in the United States where I come from,” he says.

“ They need to find ways to actually communicate beyond their differences because they live in a common society. They have to find common ground. And anthropology becomes a tool for helping you to understand all this so you can find common ground in a democracy.”

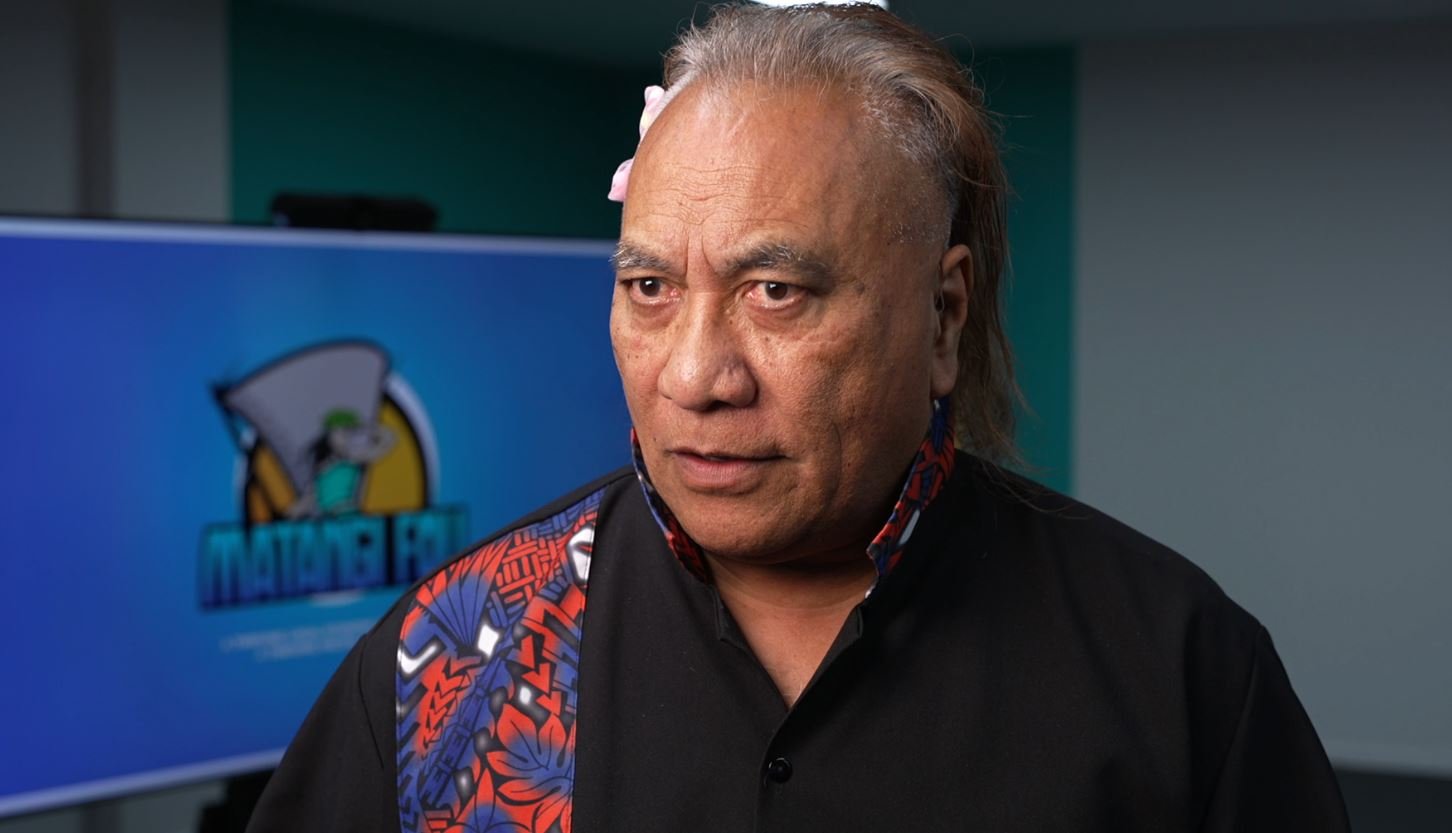

Today, just like many other Pacific islands communities, many more Pukapukans live away from their atoll in New Zealand and Australia. For community leaders like TUOTWS President Mai Nio-Aporo, he’s hopeful the research will rekindle interest in Pukapuka, its people and its history, especially among the younger generation.

“For my community, the commitment from our youth into our community is, I’m not saying all youth, but the majority of the youth commitment into our communities is not there,” he says.

“Which is sad in a way, but if they truly want to keep a hold of their heritage and their sense of belonging, they need to know the history of their culture.”

The Borofsky family have maintained close links with the atoll community over the years, Daughter amelia was a young girl when she lived on pukapuka and her recollections of that time are captured in a recent award-winning documentary, ‘The Island In Me’.

“Pukapuka is like nowhere else in the world. It’s just a really magical, magical place,” she says.

“More anthropologists have been there than any other island in the Cook Islands. And it’s because there’s a lot of rich indigenous knowledge and a lot of things still practised because it’s so hard to get to.

“My hope for the young people and the youth who are in the diaspora, both through the film, through my dad’s field notes, is to be able to connect to their ancestors.”

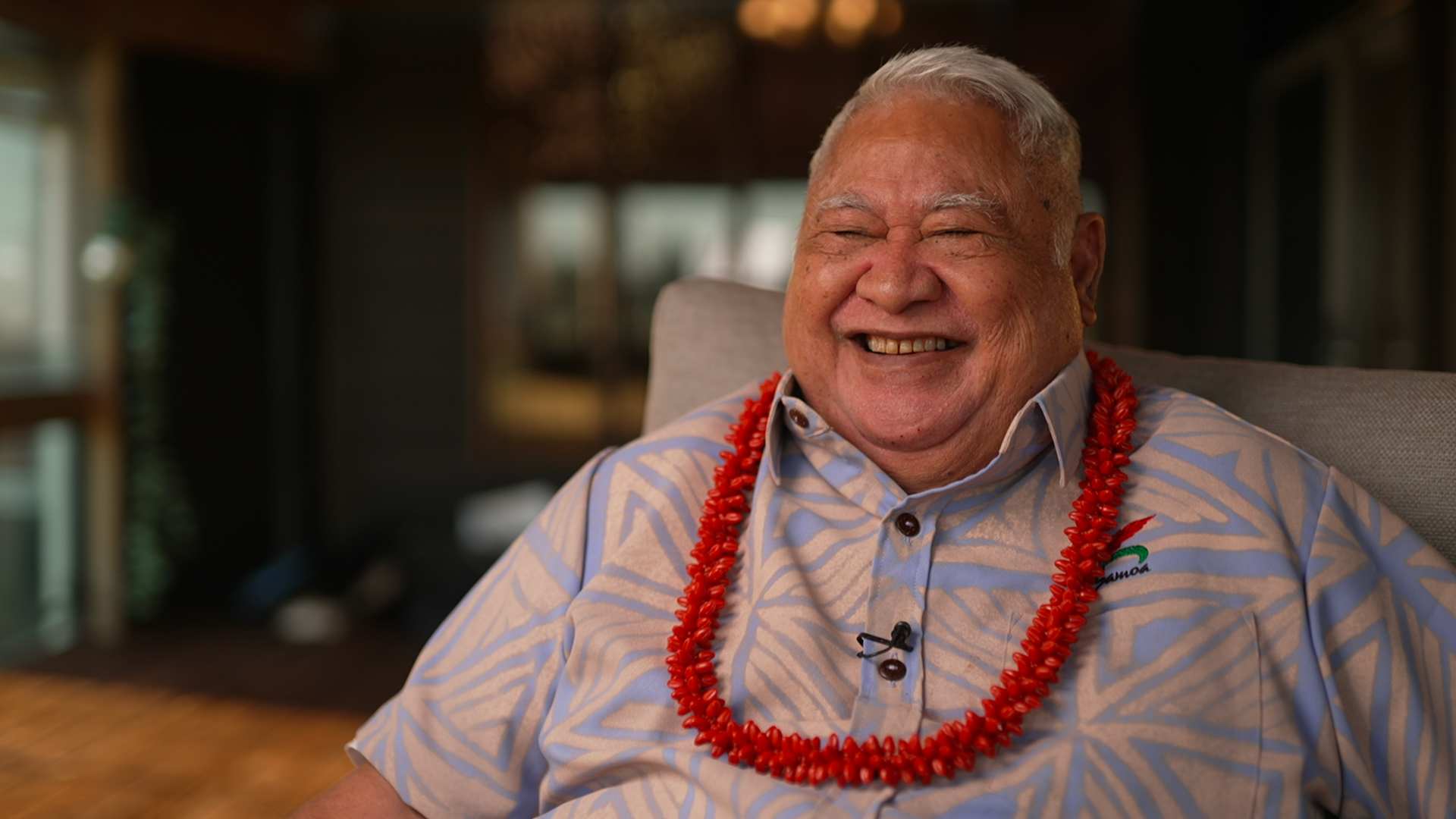

Community elder Vavaa Atiau says, the gift of the field notes to the community is a timely reminder for those in the diaspora to consider giving back to their homeland, when the time is right.

“If they achieve what they want here or in Australia, please move back. You know, go back to Wale,” he says.

“That’s where your life is, you know, help the people, help your people.”