Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air

Alfred Aholelei loves getting involved in his community, but getting around has not always been easy.

For the past 10 years, he has battled gout, a form of arthritis not uncommon for Pasifika people and primarily affects the feet.

“I could feel it all around the back of my ankle,” he says.

“It was a horrible pain actually, like trying to sleep and trying to listen to music to soothe your mind. It got to that point where the pain was so excruciating.”

At first, he was shy to open up about his experiences, but over time, he has mustered the confidence to share his story so that others can get treated early.

“Don’t be ashamed of it. It is what it is. If you have it, you have it, and you have got to not to ignore the signs,

“Because at the end of the day, it’s not only you that suffers, but your family suffers. There’s a lot of people it actually affects besides yourself.”

Samuela Ofanoa, a senior health researcher at Moana Connect, says many Pasifika gout sufferers delay seeking help due to misconceptions about the disease.

“I think it’s perceived as not as severe compared to other health conditions that have been more prioritised. However, the numbers don’t lie now,” he says.

Pharmac released a report earlier this year, the first of its kind, which revealed alarming statistics around Pacific gout prevalence and lack of access to preventative medicine.

“The numbers are coming up that the prevalence of gout for our people is the highest within our country, which is about 14%, compared to Maori and non-Pacific, which is about 4%.”

Ofanoa says one way to improve the statistics for Pasifika is by changing the perception of gout being solely linked to lifestyle.

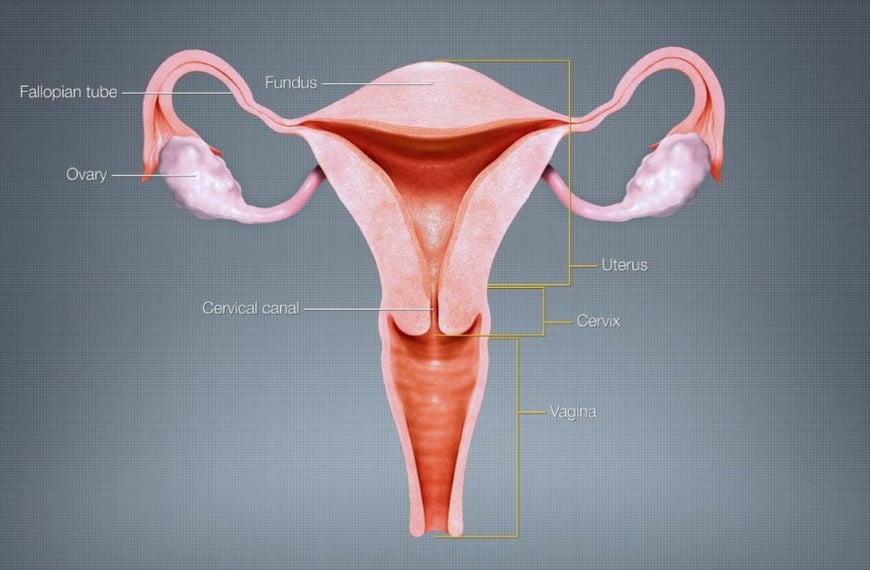

“Research has shown that Maori and Pacific have this gene that prevents our kidneys from excreting uric acid which over time when you have high uric acid in your body, it crystallises and causes gout flares within your body.”

A Pasifika gout sufferer, who we agreed not to identify, was diagnosed with gout this month at the age of 20. His doctor put it down to genetics.

“Both my parents have gout, and their parents had gout,” he says.

“The doctor gave me antibiotics for it, and that really helped, but he also advised me to change my eating habits.”

He had his first flare-up at 17, but it took him three years to come to terms with his situation and seek medical help.

“For the longest time, I believed that it wasn’t gout due to my age. I really didn’t think that gout was something that I could get as a young person, just being in a state of denial really.”

Dr Api Talemaitoga, GP at Cavendish Doctors, says the Pharmac report revealed high rates of gout-related hospitalisation. He encourages Pasifika to get treated early to avoid impacting their day-to-day lives.

“That’s really not where we want to put our resources. We need to try and treat gout in the community, at primary care to avoid hospitalisation. To go to hospital means time off work, loss of income, the person must be in a lot of pain,” he says.

“Pharmac has, through several things, shown how we should take account of ethnicity because that looks at different people and how they live and their understanding of the health system.”