Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air

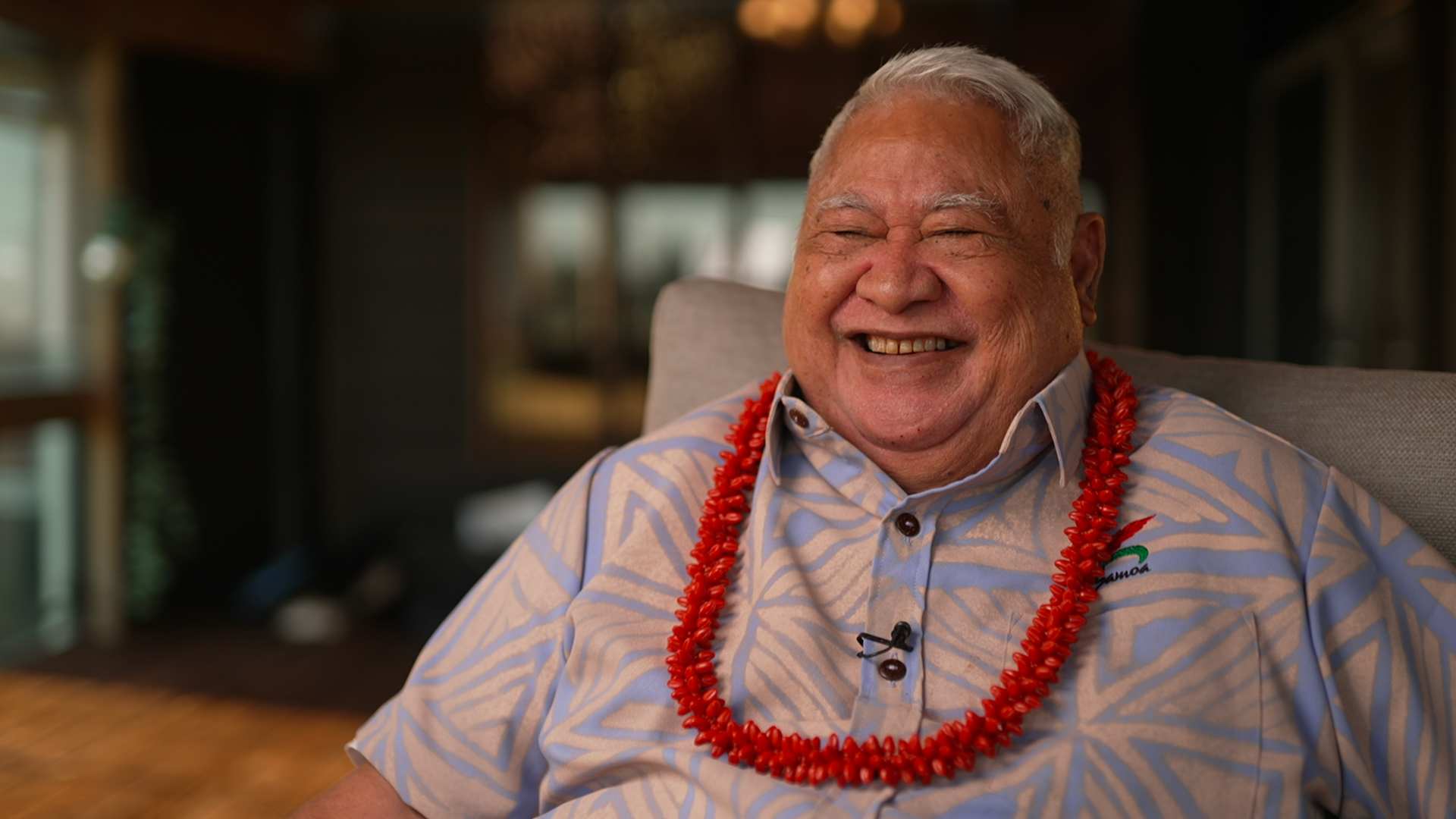

Saunoamaali’i Dr Karinina Sumeo encountered data on ethnic pay gaps for the first time in 2018, as the newly appointed Equal Employment Opportunities Commissioner for the Human Rights Commission.

The data was in the public service annual workforce report, of 403,000 people employed by the public sector. It showed Māori, Asian and Pacific people consistently earned less than Pākehā, and had lower representation in the upper tiers of management.

Pacific people were the worst affected, with a gap of 21% from Pākehā. The report showed, over the last ten years, the pacific pay gap had increased.

“I felt insulted and disrespected as a Pacific person,” Dr Sumeo says. “In the public service of all places, where you expect to be treated fairly.

“I thought – this could be happening across the entire country.”

Conversations with workers, researchers, unions and data from the Household Labour Force Survey and Stats NZ confirmed that New Zealand has a significant Pacific pay gap.

Nationwide, the average Pākehā man earns $1,442 a week. A Pākehā woman will earn $1,351. While a pacific man will earn $1,090 and a pacific woman $1,049, This is $393.20 less than a Pākehā man.

“I thought – this is a huge injustice,” says Dr Sumeo. “We need to understand why this is happening. And then we need to understand what we can do about it.”

Dr Sumeo launched the Pacific Pay Gap Inquiry in 2020. The two year project analyses workforce data, reviews literature, and speaks with Pacific workers.

Lisa Meto Fox, the inquiry project manager, says recording stories from pacific workers affected by a pay gap can be heavy. “Some of the stories that people share with us, that’s the first time that they’ve ever shared that story with someone, who isn’t, you know, perhaps their husband or wife, and they’re often deeply distressed by what they’ve experienced.”

The inquiry has received submissions from over 1200 pacific people. “CEOs, people in manufacturing, we heard from engineers just kind of like right across the board,” says Lisa. “These issues of equal pay and pay equity are everywhere.”

The inquiry commissioned a report which analysed possible causes for the Pacific pay gap, looking for explainable factors like differences in education levels, industry, and age.

The report, which was released in July this year, shows the majority of the pacific pay gap can’t be explained by these factors. It lists discrimination, unconscious bias, and non-observable or non-monetry factors as possible explanations.

“When women in executive roles are not paid the same, we accept that sexism happens.” says Dr Sumeo. “Why are we afraid to use the word racism?”

Saunoamaali’i Dr Sumeo has first hand experience of the pacific pay gap. She discovered her pay gap while working in a public service role that involved assessing pay scales.

“I noticed that my role was there, but there was a very similar role, apart from the title being different, that wasn’t there. So, just innocently, I asked my boss, where’s the other role? And they said, ‘Oh, that’s a management role on a different scale.’ I went, ‘well, why isn’t my role on that scale? It’s the same role?”’

The Pacific pay gap happens in two ways. One is when a Pacific person is paid less for the same role. The other is when Pacific people are funnelled into certain types of work or passed over for opportunities and promotions

Former unionist Lisa Meto Fox says, “I would walk into a distribution centre in South Auckland and 99% of the floor staff would be brown, largely Maori and Pacific and some other ethnic minorities. Most of the management above a team leader would be Pākehā. And so you could just see it.”

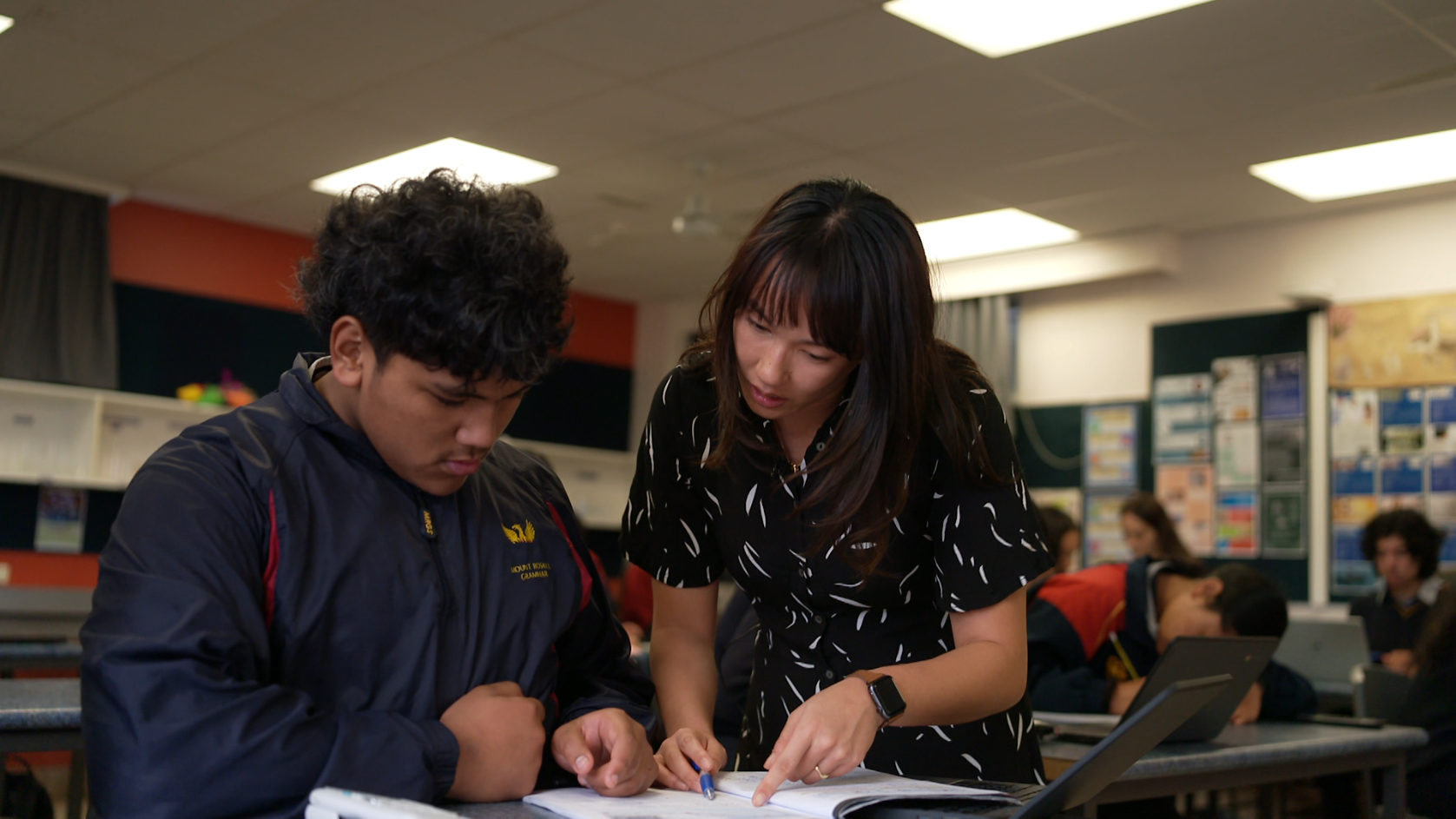

When sociology lecturer and Pasifika academic Dr Sereana Neapi noticed a shortage of Māori and Pacific teaching staff, she conducted research across universities, using a national data set that included academic grades.

The results, she says, were disappointing. “Not only were there not many of us, but when we did make it to the top of our field, we were facing a significant pay gap compared to our Pākehā counterparts. Despite being just as excellent.”

When the research was released, a Pākehā colleague proactively approached Dr Naepi and shared her letter of appointment. “We compared CVs,” says Dr Naepi, “and said ‘hang on, this doesn’t make sense.’’’ The exchange provided Dr Naepi evidence to start a conversation with her employer.

“There have been moments on this journey around the pay gap,” she says, “where I’ve been in tears. There’s a difference between intellectually knowing that there’s a pay gap and knowing that it impacts you. And I think that that’s the piece that we have to work out – how to respond.”

For Saunoamaali’i Dr Sumeo, speaking with her manager resulted in her pay gap being corrected.

“It didn’t occur to me at the time that there might be some risks,” Dr Sumeo says. “I was too angry.”

Although at the time, she acknowledges, her family owned their own house and were financially secure. The pressures of weekly food expenses, bills and rent did not stand in her way.

“We need to take the onus away from people who are suffering inequity,” she says, “and put it back on the businesses, who know every week, who’s being paid what, and can see the inequities.”

The Pacific Pay Gap Inquiry report is coming out in September. It will include recommendations on actions the government and employers can take to address the Pacific pay gap.

“The hope piece, I think, is the inquiry,” says Dr Naepi, “because the inquiry is getting people talking. It’s recording the numbers, it’s recording the stories. It’s making it a lot harder to avoid public pressure for change.”

Legislation requiring pay transparency from employers, says Lisa Meto Fox, like the public service workforce report which sparked the inquiry, will get the broadest results.

Dr Sumeo agrees, and hopes appropriate pay transparency legislation will be enacted by the current government before the end of their term.

“We’re a Pacific nation for goodness sake. We’re supposed to be a champion for Pacific. We can’t let this lie and let it dwindle on to the next generation. We have an opportunity.”

Quotes have been edited for length and clarity.