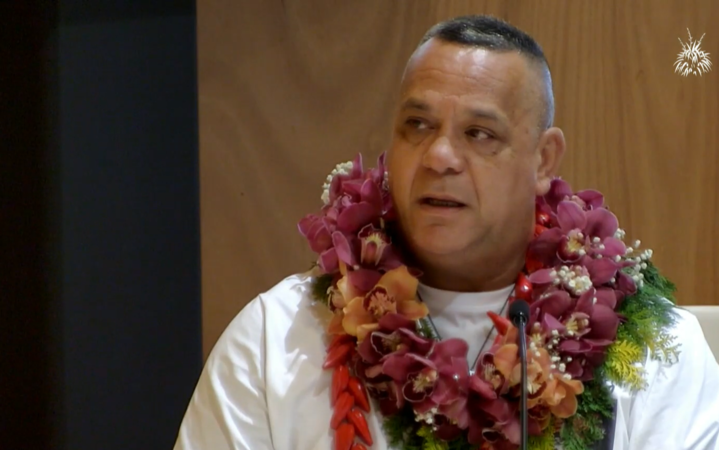

A man who was denied his true ethnicity for 30 years says he struggled mentally after finally finding out the truth.

David Crichton has told the inquiry into abuse in care that after being brought up as Māori, at the age of 30, he found out he was Samoan.

He spent most of his childhood in state care.

Crichton said he suffered all forms of abuse while in care, but the stripping of his cultural identity is the one thing that had hurt him the most.

”I spent all of my childhood, youth and the beginning of my adult life believing that I was Māori. I was denied any knowledge of my Samoan family, culture and identity.’

”I am covered in Māori tattoos because I believed that was who I was. If I had truly known of my Samoan cultural heritage I would likely be covered in Samoan tatau.”

There were no words that would ever come close to describing the impact it had on him, he said.

He requested his care file in 1997, when he and his partner were expecting their first child.

”We decided to request my care files so I could learn more about myself and where I came from. This was important for us in starting our family.”

Crichton said his mother, who was English, had significant mental health issues, which he said was known to Presbyterian Support Services and the State.

“Information provided by her should not have been relied on to any degree given her mental state.”

His records detail conversations between his mother and social workers. There is also specific reference in a child welfare report about his mother giving a lot of conflicting information.

”A major source of conflict for my mum was that my father was Samoan, that she despised him for being Samoan and that Samoans are all of an inferior social and intellectual level. She considered herself to be superior in every way to my father and felt that by living with a Samoan she had degraded herself.”

His birth certificate did not record Jim Crichton as his father.

”It states my father was unknown, but my mother knew that Jim Crichton was my father. She kept his name off my birth certificate intentionally.”

It took David many years to accept he is Samoan.

”I still struggle with it. I wasn’t raised a Samoan, but all my family is. With Māori family and friends, I’m very comfortable. They are mostly gang members and staunch people of Māori descent and they would be the first to say that I’m Māori.

”I feel like I was Māori before I was Samoan and when I’m around my friends I still feel like I’m Māori. Adjusting to the Samoan culture has been challenging.”

He said because his mother was so secretive and deceptive about his father and any extended family, he missed out on having relationships with them.

”When children are in care, they need to be made aware of their ethnicity, their true identity and of their extended family,” he said.

”I believe that the organisations responsible for my care had a duty to at least tell me who my family was, to tell me about my ethnicity, to make genuine efforts to look for my family. The responsibility increases in cases like mine, where a child spends their whole upbringing in care.

”When I found out about my Samoan heritage, I became suicidal and life was very volatile for all of us. It took me about 15 years to accept the change in my ethnicity.”

Crichton went into care when he was 15 months old. He spent time in various foster placements and residential homes.

This included the Epuni Boys’ Home and Berhampore Children’s Home. At both he suffered physical, emotional, psychological and sexual abuse.

At the age of about 13, he was put in the care of a 26-year-old, single, palagi man.

”This carer would supply us with drugs and alcohol. Marijuana and alcohol were available on a daily basis. LSD was available when he could get it. I remember taking drugs that he had me tripping out for days.”

After being in his care for about two years, the carer moved to Papua New Guinea.

Crichton became the first State Ward to be allowed out of the country to live with a caregiver overseas.

He said he did not feel safe in Papua New Guinea and went off on his own.

”I ended up running away and for about six months I lived in the bush with a group of locals. A tribe who took me to their villages and introduced me to their families and way of life.”

He was eventually tracked down and returned to New Zealand.

While he refuses to detail the abuse he experienced from the carer, he did make a complaint in 2001, disclosing the abuse, but nothing came of it.

”I know this carer went on to be convicted for child sex offending,” he said.

”Everyone saw this carer as a saint who was running programme for so-called bad kids and taking them in when they had nowhere to go, but that was far from the truth.

”There was no monitoring or outside people coming to check on us while we were in his care.”

Crichton told the Royal Commission that it was important for social workers to have life experience and understand how cultures, people, families and communities work.

”It’s more important than anything you can learn at university.”

Crichton said relatable people were needed in social services.

”I remember as a kid I could pick a liar a mile away. It was one of the skills that you learnt to survive and I know that clients working with employees in the social services will be the same way.”

He said there needed to be more accountability for wrongdoing by professionals involved in the care and protection of children.

“Institutions and government departments need to accept fault for allowing abuse to take place and for not carrying out their duties properly.”